The Denial of Voting Rights

Scroll for moreSouthern white people retained political control by denying African Americans the right to vote.

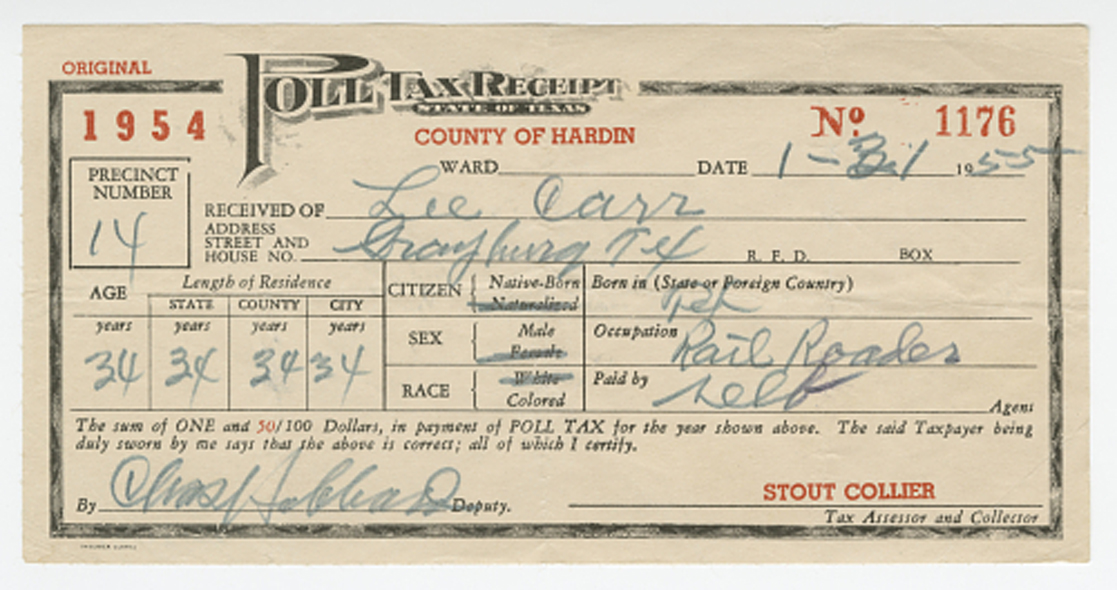

After the end of Reconstruction in 1877, the vast majority of African Americans lived in the South, where they faced systematic exclusion from the political process because they were denied the right to vote. Poll taxes, the “grandfather clause,” and felon disenfranchisement were legal barriers to the ballot box, and economic retaliation and violence was used to terrorize those who dared to challenge those obstacles. As one Black man from Georgia said in the 1930s, “I can’t pay a poll tax, [so I] can’t have a voice in my own government.” For many leaders and activists of the Civil Rights Movement, gaining the right to vote was the way to effect broad and lasting change in American society. The fight for voting rights was a major focus of the civil rights era and a primary target of white opposition.

Photo: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (Carr Family Gift)

The Fifteenth Amendment, adopted in 1870, barred racial discrimination in voting. But when former Confederates regained legislative power in the South in the 1890s, they worked quickly to disenfranchise Black citizens by enacting felon disenfranchisement laws, selectively-enforced literacy tests, poll taxes, discretionary registration systems, and white-only primaries.

African Americans who tried to overcome these obstacles risked economic retaliation. Newspapers in many communities printed daily the names of Black people who tried to register to vote, so they could be harassed, threatened, evicted, and fired. Black people working as sharecroppers were especially vulnerable, and many were evicted and left homeless for attempting to vote. White Citizens’ Councils distributed lists of registered voters to white merchants so that African Americans would be refused basic necessities and employment.

On August 31, 1962, activist and sharecropper Fannie Lou Hamer and 17 other Black people tried to register to vote in Indianola, Mississippi. She and her husband were evicted from the plantation where they had lived and worked for 18 years. Less than two weeks later, their new home in Ruleville was attacked with gunfire. Undeterred, Mrs. Hamer returned to register in December, telling the courthouse clerk, “Now you can’t have me fired ‘cause I’m already fired, and I won’t have to move now, because I’m not living in no white man’s house.”

Voting rights were a major goal of the Civil Rights Movement, and the Selma to Montgomery March was waged to bring attention to the need for federal voting rights legislation. But the disenfranchisement of Southern Black people translated into the super-enfranchisement of Southern white people. In a 50 percent Black Southern district where no Black people voted, each white vote held twice the influence of a Northern vote cast in a fully enfranchised district.

Southern white people were deeply invested in disenfranchisement as a way to maintain the region’s outsized influence over national politics. Even after the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965, violent opposition continued. On January 10, 1966, Klansmen set fire to the Mississippi home of Vernon Dahmer, a successful Black businessman active in the voting rights movement, then shot up the house. Mr. Dahmer returned fire from his doorway while his family escaped; he died the next day from damage to his lungs.

Women reading sample ballots in an Alabama church following the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

Photo: Getty Images/Flip Schulke Archives