The Trauma of Jim Crow

Scroll for moreAfrican Americans were traumatized by the constant humiliation, harassment, and threats of violence they experienced under Jim Crow.

For generations after the abolition of slavery, Jim Crow laws represented a formal, codified system of racial apartheid that dominated the American South. These laws invaded every aspect of public life and their enforcement ensured that Black people faced daily humiliation. “Whites Only” and “Colored” signs were constant reminders of the racial caste system that confined all Black people and those perceived as trying to violate that system faced the threat of deadly violence.

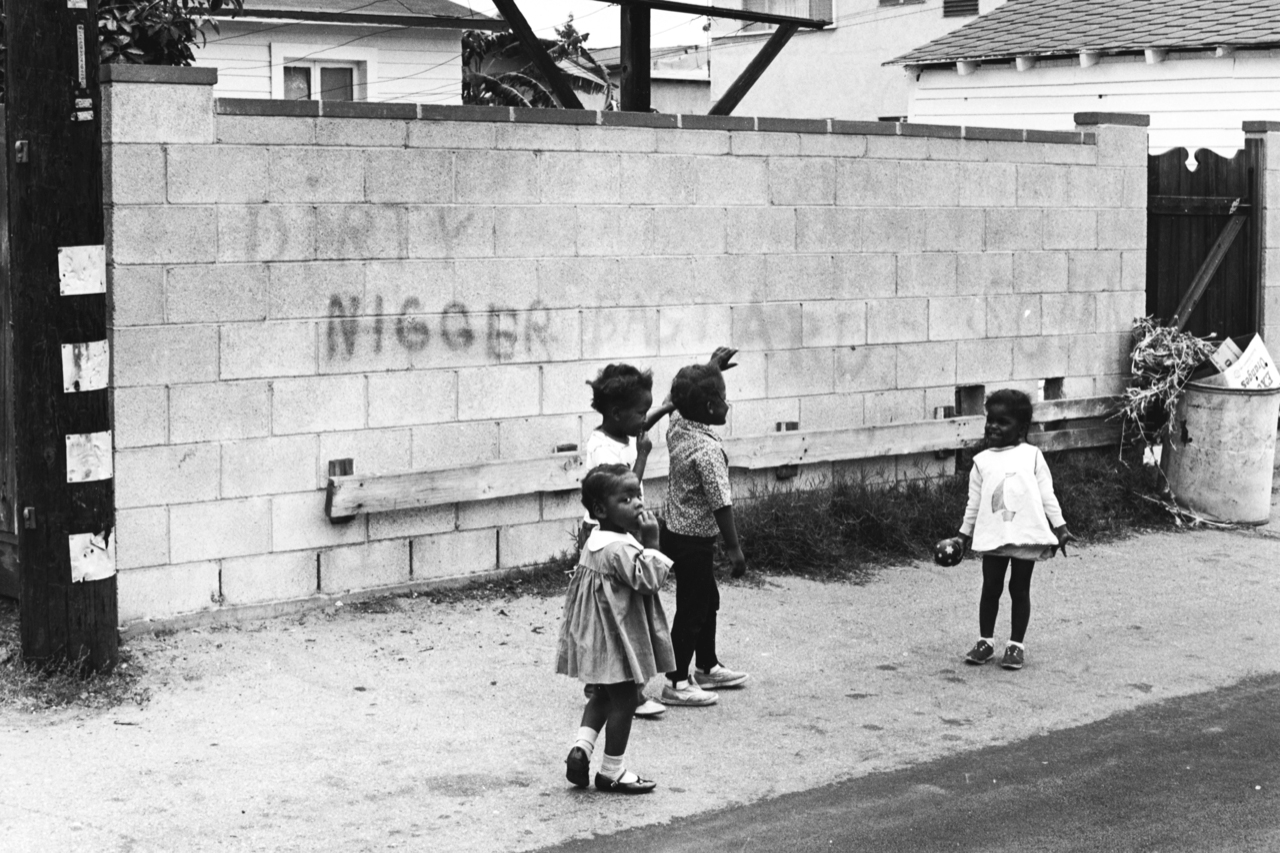

Photo: Joe Schwartz

The racial hierarchy enacted by Jim Crow segregation laws was held firmly in place by the threat of public humiliation, physical violence, and death. As civil rights activist Diane Nash recalled, “[T]he segregated South for Black people was humiliating. The very fact that there were separate facilities was to say to Black people and white people that Blacks were so subhuman and so inferior that we could not even use the public facilities that white people used.”

In 1944, Zora Neale Hurston, a Black writer and anthropologist, visited the office of a white physician in New York. Later, in an essay titled “My Most Humiliating Jim Crow Experience,” she recounted being examined in “a closet where the soiled towels and uniforms were tossed.” Sitting on a chair wedged between the wall and a pile of dirty linen, Hurston “did not get up and sweep out angrily as I was first disposed to do.” Instead, she endured the blatant racism as the white doctor examined her in a rushed and desultory manner. Hurston was one of countless Black Americans traumatized by the indignity of Jim Crow.

During this time, white people routinely harassed, humiliated, and harmed Black people in the name of “separate but equal.” Every day for three quarters of a century, African Americans lived under the scrutiny of “the Jim Crow gaze,” a dead look that marked “the refusal, evident in the aggressor’s eyes to see you as a worthy, equal subject.” As early as 1970, mental health professionals acknowledged that childhood experiences of being targeted by racism constituted a “pervasive and serious menace to mental health.”

When the Little Rock Nine returned to Central High School in 1987, three decades after they integrated the school in the face of violent mobs and under military guard, Melba Patillo Beals clearly remembered the terrifying climb up to the front door, “trapped between a rampaging mob, threatening to kill us to keep us out.” And the trauma did not end once they entered the schoolhouse. “What’s worse than to be rejected by all your classmates and teachers?” Beals asked, recalling her persistence. “I got up every morning, polished my saddle shoes, and went off to war.”

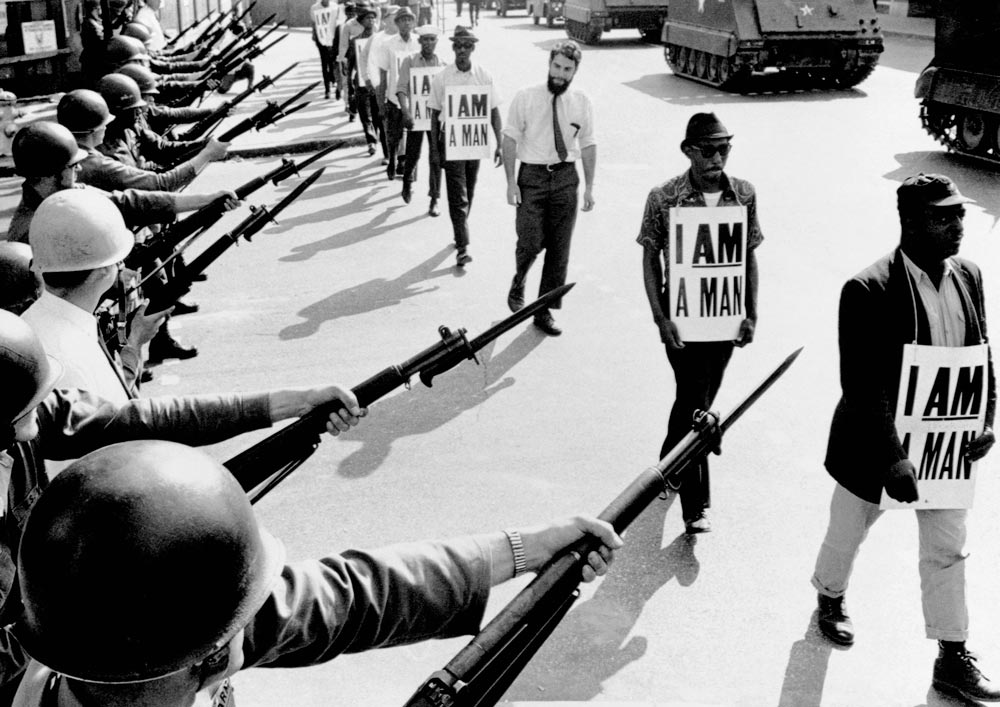

National Guardsmen brandish bayonets as sanitation workers protest dangerous working conditions in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1968.

Photo: Getty Images/Bettmann