Medical Inequality

Scroll for moreBlack patients faced discrimination and structural inequality even when they sought basic medical care.

American racism was deadly for African Americans. Black patients faced discrimination and structural inequality even when they sought basic medical care to treat illnesses or protect their lives. Prejudiced white physicians regularly delivered substandard care to Black patients and then dismissed the harmful results as evidence of pathological racial differences or blamed the patient. Aspiring Black doctors were routinely denied admission to medical training programs and denied licenses to practice medicine. African American communities displayed disproportionate morbidity and mortality rates due to their inability to secure quality medical, surgical, pediatric, and obstetric care.

Hale Infirmary, a segregated hospital for Black patients in Montgomery, operated until 1958.

Photo: Alabama Department of Archives and History

In 1944, social scientist Gunnar Myrdal observed, “Area for area, class for class, Negroes cannot get the same advantages in the way of prevention and care of disease that whites can.” For generations in America, medical discrimination was common and legally sanctioned. Federal funding policies like the Hill-Burton Act of 1946 were designed to improve the hospital bed-to- population ratio in rural areas, but operated under the “separate but equal” principle and primarily benefited white people. In 1962, Senator Jacob Javits of New York reported, “Segregated hospitals and segregated wards have resulted in over-crowded conditions and substandard facilities for many Negro patients.”

In November 1931, Juliette Derricotte, a dean at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, was in a serious car accident while driving near Dalton, Georgia, with three students. Nearby Hamilton Memorial Hospital refused to admit Black patients, so the injured were treated in the home of a local Black family – though Ms. Derricotte and one student, Nina Johnson, was critically injured. Six hours later, a hospital 35 miles away in Chattanooga, Tennessee, agreed to accept them, but it was too late. Ms. Derricotte died en route to the hospital and Ms. Johnson died the next day. NAACP Secretary Walter White later declared that the incident displayed “the barbarity of race segregation in the South . . . in all its brutal ugliness.”

To combat medical disparities that led to death and widespread illness in the Black community, civil rights and community groups began sponsoring Negro Health Weeks as early as 1914. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited federally-funded programs and institutions from discriminating on the basis of race, and the creation of Medicare in 1965 made nearly all hospitals federally-funded. Between 1956 and 1967, the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund successfully litigated a series of cases to eliminate overt discrimination in hospitals. These civil rights victories achieved improved access and care for patients of color nationwide, but medical experimentation on African American patients continued into the 1970s, and disparate medical access and outcomes persist in minority communities to this day.

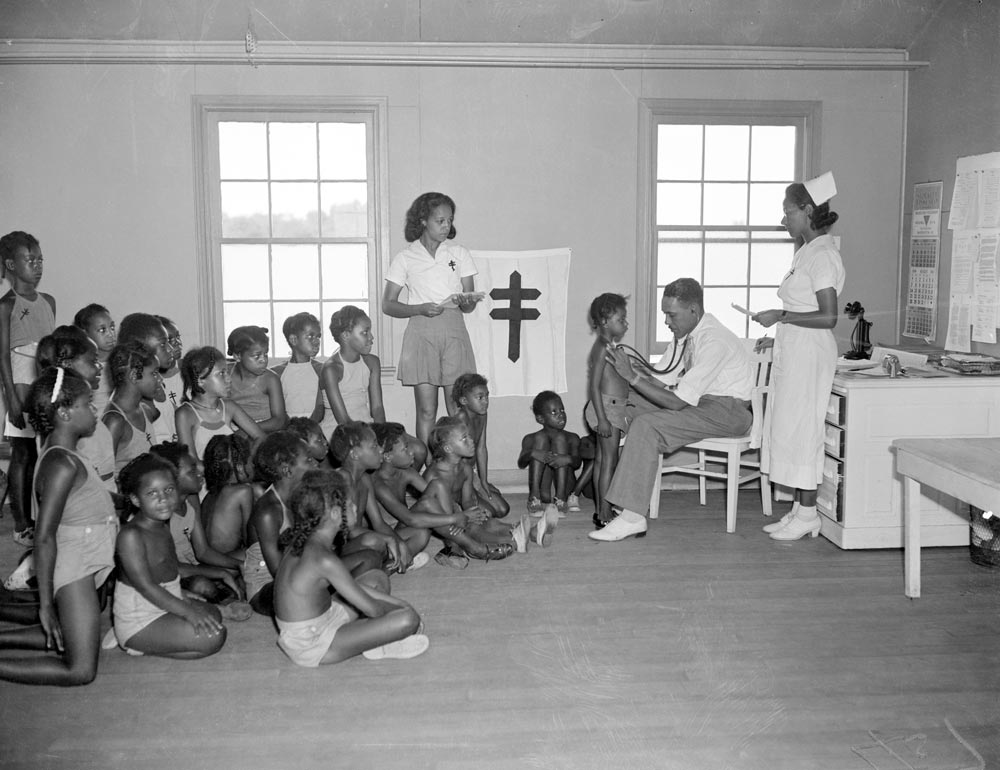

Patients treated for tuberculosis in 1938. Black children with tuberculosis faced extremely high morbidity rates as compared to white children.

Photo: Getty Images/Bettmann