Segregation Academies

Scroll for moreTo avoid integration, Southern states used public money to create all-white private schools.

After the Supreme Court ruled in 1954 that segregated public schools were unconstitutional, federal courts began ordering Southern schools to integrate. To circumvent these orders, Southern states used public money to fund all- white private schools and sometimes even closed the public schools. Hundreds of private “academies” sprung up throughout the South, creating two school systems: one public and Black; one private and white. Many persist today.

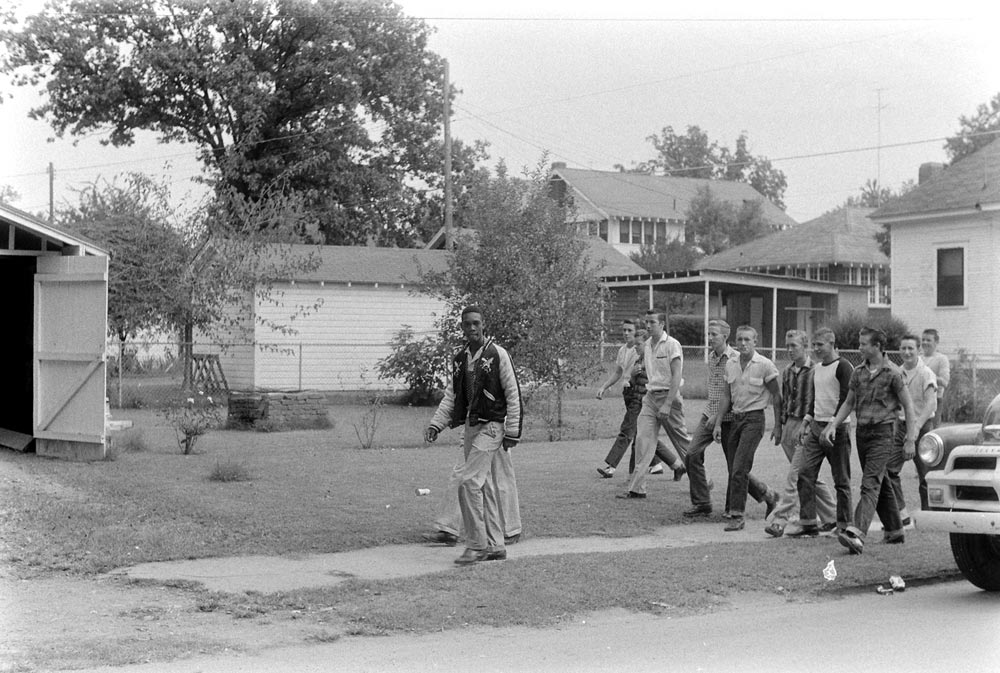

On August 30, 1956, a white mob hung an African American effigy at Mansfield High School in Texas.

Photo: Bettmann/Getty Images

As white students withdrew from public schools en masse to avoid integration after Brown, many Southern states created segregated “private” schools and directed state grants and county tax credits to cover tuition expenses. Montgomery Academy opened in 1959 as Alabama’s first segregation academy. Housed in the old Governor’s mansion, the school welcomed “boys and girls of white parentage.” Many similar schools soon opened throughout Montgomery and across the South.

In May 1959, after a federal order to integrate, officials in Prince Edward County, Virginia, instead closed the public school system. More than 90 percent of local white students enrolled in new, state- funded segregated private schools. The county’s more than 1,700 Black students had no state-funded educational option until the Supreme Court overturned Virginia’s tuition grants and forced Prince Edward County schools to reopen five years later.

Even when federal courts struck down state efforts to selectively close public schools to avoid integration, those rulings could not stop white students from fleeing. In 1963, after a federal court ordered immediate integration in Macon County, Alabama, Governor George Wallace temporarily closed Tuskegee High School to prevent 13 Black students from enrolling. When the school reopened, all 275 white students withdrew, and most used state-funded scholarships to enroll at Macon Academy – a newly formed, all-white private school that now operates as Macon East Academy in Cecil, Alabama.

Nearly 15 years after Brown, many in the Deep South continued to evade integration. In Mississippi, enrollment in private academies quadrupled during the 1969-70 school year and continued to increase well into the 1970s as new schools opened in response to court-ordered desegregation. In Indianola, Mississippi, after a federal judge ordered all-white Gentry High School integrated in 1970, not a single white student showed up for the first day of class; they had all enrolled at Indianola Academy.

Between 1964 and 1975, educational historians estimate that at least half a million white students withdrew from public schools to avoid mandatory desegregation. These segregation academies and their legacies live on throughout the South. According to a 2014 report, “In Tuscaloosa [Alabama], nearly one in three Black students attend a school that looks as if Brown v. Board of Education never happened.” In Mississippi today, more than 35 segregation academies survive, each of which has less than 2 percent Black enrollment.

A group of white segregationists harass two Black students in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957.

Photo: Getty Images/Ed Clark