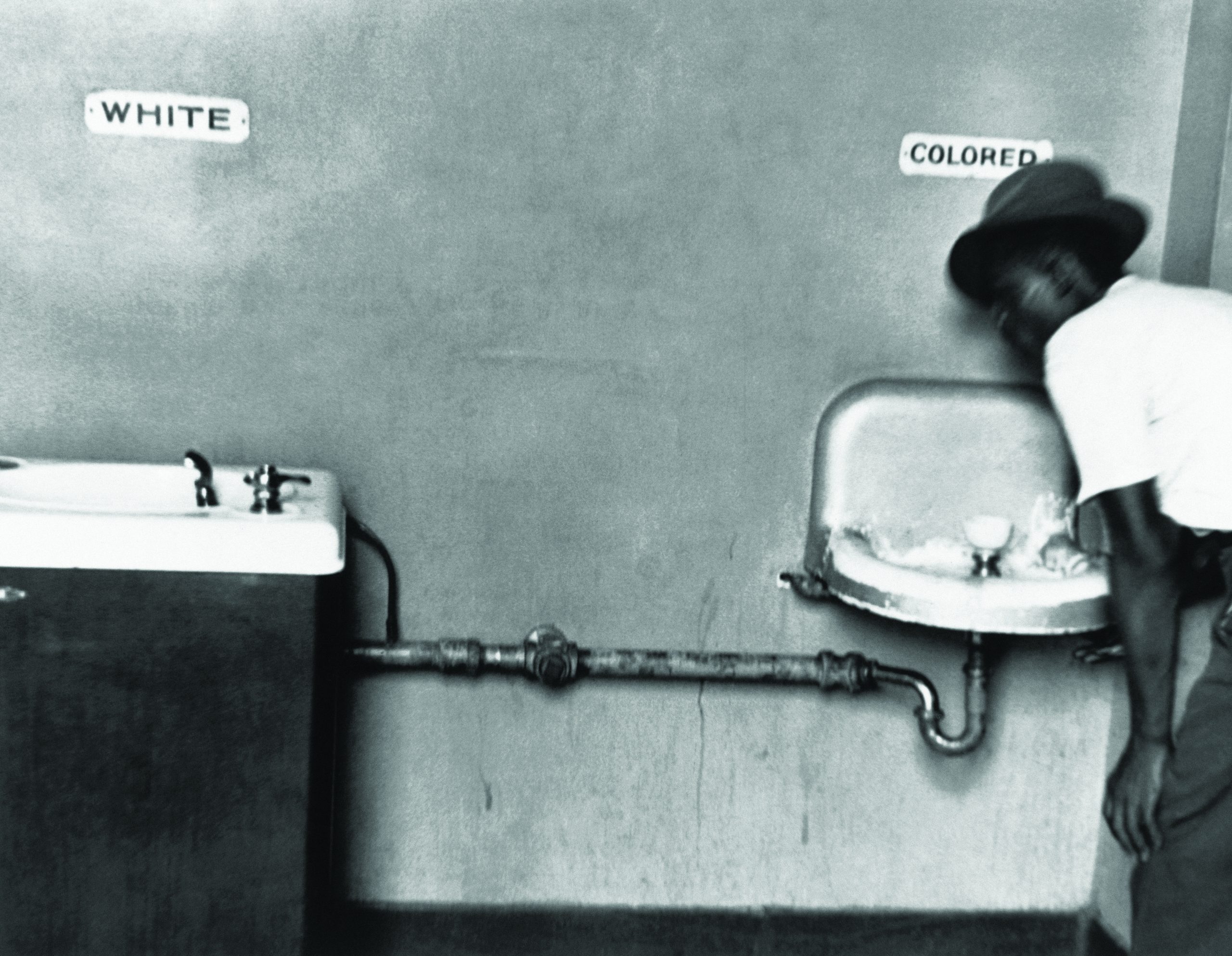

Separate by Law

Scroll for moreRacial segregation was not about personal prejudice – it was mandated and enforced by local and state laws.

The narrative of racial difference and white supremacy created to justify slavery was not abolished by the Emancipation Proclamation or the Thirteenth Amendment. Instead, it outlived slavery and Reconstruction. By the end of the 19th century, Black people were widely disenfranchised in the South. Officials elected by all-white constituencies passed a patchwork of state and municipal statutes requiring racial separation in major and mundane areas of life and relegating Black Americans to a place of second-class citizenship. This “Jim Crow” system was a major inspiration for – and target of – the Civil Rights Movement.

Photo: Elliott Erwitt/Magnum Photos

The term “Jim Crow” initially referred to a style of minstrel show in which white performers caricatured Black life for the entertainment of white audiences. By 1890, the term described a system of laws that proscribed the lives and possibilities of Black people throughout the South. All aspects of life were governed by a strict color line, from the most central and important to the most mundane and tedious.

In 1901, a white woman and Black man were arrested in Atlanta, Georgia, after two police officers accused them of talking and walking together on the street. Interviewed afterward, the white woman was indignant — not at the law, but at the suggestion that she would ever share the company of a Black man in public. “I stopped and [a police officer] asked why I talked to a negro,” she told the press. “I told him I was a southern born woman, and his insinuations were an insult.”

As historian Leon Litwack wrote: “For all African Americans, Jim Crow was a daily affront, a reminder of the distinctive place “white folks” had marked out for them—a confirmation of their inferiority and baseness in the eyes of the dominant population. The laws made no exception based on class or education; indeed, the laws functioned on one level to remind African Americans that no matter how educated, wealthy, or respectable they might be, it did nothing to entitle them to equal treatment with the poorest and most degraded whites.”

These reminders were plentiful. In Ensley, Alabama, barbers were required to use separate razors, brushes, linen, and chairs for Black and white patrons, while Birmingham outlawed interracial games of pool, cards, dice, dominoes, checkers, or billiards. Arkansas and Florida required the segregation of Black and white prisoners, and Louisiana law made circuses maintain separate, racially-segregated tent entrances and ticket booths. Segregated hospitals, public transportation, and public schools were law throughout the South, and a 1941 Florida statute even required that textbooks used by white and Black students be stored separately.

Widespread and inescapable, Jim Crow confined Black Americans for generations after the end of slavery. Determination to overturn those barriers inspired many who came to lead the Civil Rights Movement. “When growing up, I saw segregation. I saw racial discrimination,” recalled civil rights activist and congressman John Lewis. “I saw those signs that said white men, colored men. White women, colored women. White waiting. And I didn’t like it.”

A family pauses outside of a segregated waiting room at the Sante Fe Depot in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, in 1955.

Photo: AP Photo