Violent Opposition to Equality

Scroll for moreUnchecked racialized violence helped maintain America’s system of racial separation and hierarchy for decades.

Like lynchings of the era before, brutal violence and racial terrorism was widely encouraged and used without consequence to preserve racial segregation. Mob violence waged by white segregationists throughout the South drew national attention and brought school desegregation to a halt across the region in the early days of the movement. That violence spread nationwide in later years.

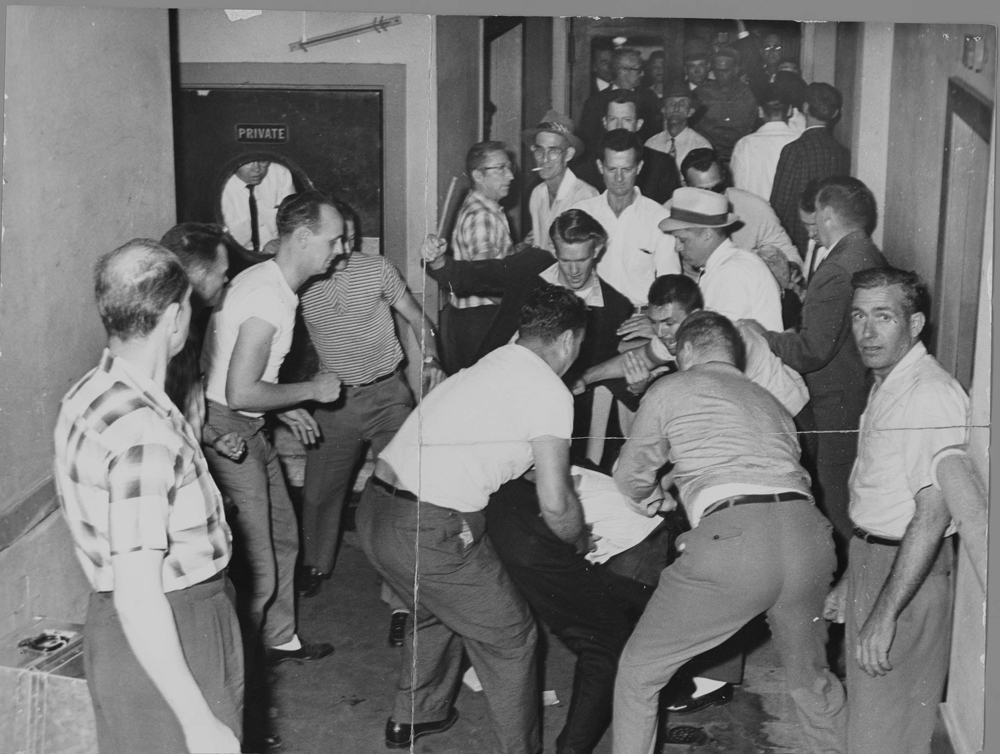

A white mob beats Freedom Riders in Birmingham, Alabama, in May 1961.

Photo: FBI

Up to a quarter of white Southerners polled admitted that they favored violence, if necessary, to resist school desegregation. In 1956, Ku Klux Klan rallies drew hundreds, even thousands, in South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Florida – states where the supremacist group had recently been considered extinct. With that increase in membership came brutal attacks. In 1957, six Klansmen castrated a Black man in Birmingham, Alabama, after taunting him for “think[ing] nigger kids should go to school with [white] kids.”

The White Citizens’ Council began in Mississippi in 1954 and launched chapters throughout the South, which quickly attracted more than 250,000 members determined to defend “states’ rights.” The councils claimed to repudiate violence, but a handbill circulated at a large council rally in Montgomery, Alabama, denounced desegregation and declared, “When in the course of human events it becomes necessary to abolish the Negro race, proper methods should be used. Among them are guns, bow and arrows, slingshots and knives.”

From 1955 through 1963, Black activists in Birmingham, Alabama, were targeted in at least 21 bombings, including multiple attacks on movement leader Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, and an explosion at 16th Street Baptist Church that killed four young Black girls and two young Black boys in the violent aftermath. In 1966, Black students who tried to integrate public schools in Grenada, Mississippi, faced a white mob that chased them through the streets, severely beating them with chains, pipes, and clubs in violence that continued for days without intervention from law enforcement.

On July 7, 1964, five days after the Civil Rights Act outlawed discrimination in public accommodations, a group of Black teenaged boys sat in the “white” section of a downtown Bessemer, Alabama, department store lunch counter and ordered. In response, a group of white men attacked them with bats, injuring one boy so badly he had to be hospitalized.

Racial violence was not restricted to the South. African Americans trying to move out of traditionally Black neighborhoods faced 213 violent attacks in Philadelphia during the first six months of 1955, and Black Los Angeles residents faced more than 100 incidents of move-in related violence between 1950 and 1965. In September 1974, after court-ordered busing began to integrate Boston public schools, white mobs attacked buses carrying Black students to white schools by hurling eggs, bricks, and bottles.

Like lynchings, mob violence, bombings, and murder committed to oppose civil rights progress were bold, public acts that implicated the entire community.

A 12-year-old was blinded by the bomb set off in the basement of the 16th Street Church in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963.

Photo: Frank Dandridge/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images